Knee pain is prevalent, yet finding a clinician with a true understanding of the knee is rare. Paradoxically, the knee stands out as one of the most misconceived and mishandled areas of the body.

More Than a Hinge Joint

Moreover, the conventional analogy likening the knee to a door hinge is fundamentally flawed. Picture a door devoid of hinges, relying instead on tape and rope for its motion. Visualize the intricacy: robust tape and rope meticulously facilitating seamless, calculated movement. Disrupting this delicate balance, cutting one rope, leads to friction—a discomforting, dull ache in the knee, sometimes escalating to shooting pain. Prolonged friction becomes the catalyst for meniscus wear and, eventually, the ominous bone-on-bone scenario.

In this analogy, ligaments represent the pieces of tape, while muscles embody the rope. Together, they contribute to localized stability in the knee. The harmonious interplay of ligaments and muscles is vital for optimal movement. The key takeaway is clear—discard the notion of a hinge; instead, embrace the concept of robust ligaments and muscles as the cornerstone of knee stability.

Local Knee Stability: Ligaments and Muscle

The significance of "local" stability in the knee, as provided by ligaments and muscles, becomes more apparent when we zoom out to consider the broader picture. The knee is enveloped by the hip and ankle joints, which contribute to the non-local stability crucial for its proper function. Maintaining proper knee alignment—ensuring the kneecap consistently points in the direction of the toes—requires robust buttock muscles, specifically the gluteus maximus and medius. The ankle, too, relies on a strong tibialis anterior to preserve alignment. The alignment dictated by the hip and ankle joints becomes a determining factor for the longevity of the knee. If alignment falters, the risk of injury increases; conversely, optimal alignment translates to increased durability for the knee.

Non-local Knee Stability: Hip and Ankle

The genesis of knee dysfunction is often traced back to weakness and immobility in the hip and ankle joints. Weak hips and ankles collapsing inward can give rise to knock knees (genu valgus). This altered posture imposes excessive strain on the hamstrings, quadriceps, and IT band, leading to muscle strains. Additionally, it disrupts the tracking of the kneecap (patella), resulting in anterior knee pain (patellofemoral pain syndrome). Once again, these issues at the knee are predominantly an outcome of complications originating in the hip and ankle joints. Weak and immobile hips and ankles render the knee more susceptible to traumatic injuries such as ligament sprains (ACL, PCL, MCL, LCL, MPFL) and meniscus tears. Accumulated injuries further heighten the vulnerability of the knee to cartilage wear-down and arthritis.

In summary, the hip and ankle joints play a pivotal role in predisposing the knee to injury. Injuries to the local knee structures perpetuate friction within the knee, accelerating the breakdown of the knee joint. While this understanding constitutes a significant part of the overall picture, one more crucial aspect warrants emphasis— the VMO (vastus medialis oblique).

The Piece to the Puzzle: the VMO

This VMO, one of the four quadriceps muscles located on the front of the thighs, specifically near the inner thigh, attaches to both the thigh bone (femur) and the kneecap (patella). Its function involves aiding in the extension or straightening of the knee.

In the context of joint injuries, a consistent pattern emerges: when an injury occurs certain muscles deactivate, while others tighten and go into spasm. Vladimir Janda, through extensive research, identified these recurring muscles, termed phasic and tonic muscles. In the case of the knee, a notable occurrence is the deactivation of the VMO (vastus medialis oblique) when the joint is injured. The VMO, situated closer to the inner thigh, pulls less than the other quad muscles positioned on the side of the thigh. Consequently, these overpower the VMO, pulling the kneecap towards the outer side of the leg. This disparity, whether subtle or severe, presents a significant issue, akin to driving a car that drifts to the side of the road, experiencing the bumpy treads. Continuing on such uneven terrain would inevitably lead to tire wear.

Moreover, this phenomenon is a key contributor to the pain associated with knee injuries. Regardless of whether the injury involves a meniscus tear, ligament sprain, or arthritis, the actual pain is often not primarily caused by the affected meniscus or ligaments. Instead, it stems from the weakened VMO and the lateral tracking of the patella. This scenario exacerbates irritation to the knee's fat pad, a structure that is not only present but heavily innervated.

The Proof is in the Research

Returning to the analogy of a door with tape and rope for hinges, a surprisingly effective technique is medial patella taping. This evidence-based method involves applying a piece of KT tape across the kneecap directing a lateral pull. If it helps, this cycle of dysfunction is likely a factor. Research shows that medial patella taping works for pain, but it is figuratively and somewhat literally just a Band-Aid.

Illustrating this point, an unconventional experiment was conducted by a daring doctor several years ago. His brother used a scalpel to poke various structures within the doctor's own knee, including the ACL, PCL, meniscus, LCL, and more. Surprisingly, these major structures did not elicit pain. The true source of pain was identified as the fat pad. Anything that agitates this fat pad tends to perpetuate significant pain in the knee. So with most injuries to the knee, the actual injured tissue may not cause the majority of the pain. The VMO usually shuts off causing poor mechanics, consistent inflammation, and increased irritation to the more painful structures like the fat pad.

Treatment Backed by Science

We can break treatment down into three major components: the injured structures of the knee (ligaments, tendons, meniscus, arthritis), the neighboring structures that influence knee alignment (hip and ankle), and the VMO. Typically, I address these in that order, giving due consideration to the injury.

Step 1: Treat Local Issues of the Knee

As far as the injured structures go, you want to get cleared to rehab by a medical professional. Once you’re in the clear, the key is to proceed slowly and ease into activities. This aligns with the mosaic model of treatment applicable to various overuse injuries. Gradually introducing safe activities allows the tissues to adapt over time. Rushing or overdoing it can lead to pain, and pain may signify friction, potentially resulting in more wear and tear. It's essential to avoid unnecessary pain. Embrace a new mantra: it's no longer "no pain, no gain"; it's about less pain and more gain. Keeping this in mind, time becomes a valuable ally.

Regrettably, patience is not always a virtue in the American approach to health. The desire for a quick and easy fix often leads to the consideration of pain pills and surgery. However, a cautious approach is warranted in this line of thinking. Pain pills may dull the pain, but this poses a challenge: how will you discern if you're causing friction and damage to the joint when you can't feel the pain? Pain serves a purpose—it signals when to take it easy.

Regarding surgery, once you embark on that path, there's often no turning back. The question arises: is it genuinely beneficial? An intriguing study sheds light on this. A group of patients with meniscus tears underwent surgery, while another group underwent sham surgery. The latter involved anesthesia, an incision with stitches, but NO actual repair. Surprisingly, both groups showed comparable improvements. This prompts us to consider the role of the placebo effect, but equally significant is the post-surgery rehabilitation process.

After surgery, individuals typically follow protocols that involve taking it easy initially and gradually reintroducing activities. These protocols may contribute more to successful outcomes than the surgeries themselves. Speculation suggests that this mirrors a mosaic model where a gradual reintegration allows tissues to readapt over time. To delve deeper into these concepts, consider exploring sham surgery studies for a comprehensive understanding. The evidence suggests that there's more to the story than meets the eye.

Step 2: Treat Non-local Issues at the Hip and Ankle

So, the initial phase involves protection and allowing the body to heal. As progress unfolds, attention can shift towards addressing issues in the hip and ankle. For many individuals, incorporating stretches for hip abduction, hip extension, and ankle dorsiflexion are beneficial. Strengthening exercises for the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and tibialis anterior are also essential to improve non-local knee stability. Gradually increase the intensity, aiming for 4 sets of 12 reps, three times a week on nonconsecutive days, with 2-3 minutes of rest between sets. This structured approach is what we term a therapeutic rep scheme. If you want to delve deeper into these principles, Ola Grimsby offers valuable insights. However, if your recovery involves doing 3 sets of 8 or 10 reps, it might be worthwhile to scrutinize your therapist's expertise.

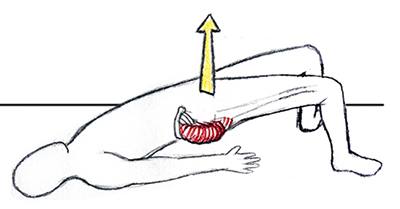

Bridges (gluteus maximus): Lay on your back with your knees bent and your knees and feet apart. Tighten your buttocks muscle and make that muscle carry you through the movement as you raise your hips up into the air. Hold it there for a second, then return to the starting position, relax for a second, and repeat. You may use a weight atop your hips for added resistance as safely tolerated.

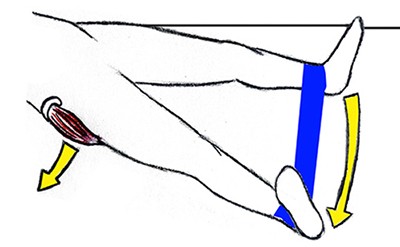

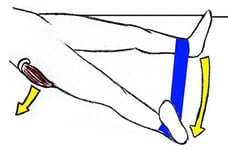

Bilateral hip abductions (gluteus medius): Lay on your back with your legs straight. Tighten your buttocks muscle and make that muscle carry you through the movement as you slide your legs apart like windshield wipers. Hold it there for a second, then return to the starting position, relax for a second, and repeat. It is important to keep your toes pointed straight or slightly inward throughout the movement. Do not allow your toes to point out. You may use ankle weights or a theraband around both ankles for added resistance as safely tolerated.

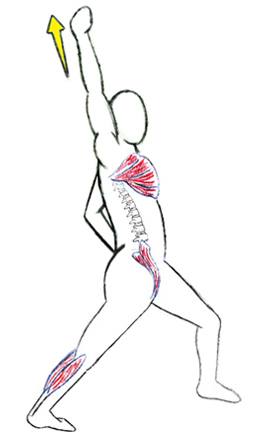

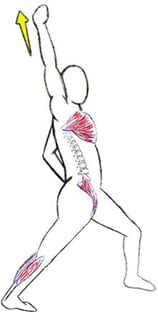

Psoas stretch: Split your stance until you feel a stretch on the front of your back leg. This stretches your rectus femoris muscle. Next—with the hand on the same side of the back leg, punch your fist into the air and tilt your torso back. This stretches your psoas muscle. A tight psoas can cause back, hip, and knee issues so this is an important stretch. Hold for 30 seconds to 4 minutes after which there is a diminishing return.

Step 3: Go Slow, Not Low, Activate the VMO

The third piece of the puzzle is strengthening the VMO (vastus medialus oblique). Despite its significance, clinicians often fail in strengthening the VMO due to inappropriate exercise selection. To properly isolate this muscle, a good clinician should leverage EMG research. This requires great precision when performing exercise. Let’s look at slow eccentric mini-squats. Adopt a slow, not low, approach, emphasizing very shallow yet deliberate mini-squats (see picture ). This method stands out because it stresses the muscle metabolically without compromising the joint, making it a therapeutic exercise. Going slow activates the VMO more than other quad muscles. As proficiency improves, a TheraBand can resist terminal knee extension, or progression to one-legged exercises can isolate the VMO even further.

Single leg squats (quadriceps): Grab ahold of a chair, grab bar, counter, or walker. Kick one leg back in a straight line with your spine. While standing on the other leg, very slowly descend part of the way down. Go slow, not low on the way down and come back up at a normal speed. The lower you go, the more compression you place on your knee joints, so you should not descend all the way. Instead, go slow on the way down which will stress the muscle metabolically and focus more contraction on the vastus medialis which is the most therapeutically beneficial quadriceps muscle. You may use a TheraBand behind the knee for added resistance as safely tolerated.

This nuanced approach surpasses the common practices found in many physical therapy clinics, where exercise selection often lacks therapeutic intent, resulting in suboptimal outcomes. Clinicians may need to broaden their perspectives for better results.

Conclusion

There's a saying in medicine—invest your health in gaining wealth, and later spend your wealth regaining health. As a clinician who has seen this play out countless times, I urge you to make a small investment in your own wellbeing. Bottom line, if you’re going to strengthen or perform a rehab regimen, you should do so in a way that improves your overall strength and aesthetic while simultaneously improving the health of your joints and decreasing your overall pain.

If you're grappling with knee pain and need assistance, I'm more than willing to help. My online therapy platform, PTrehabdoc.com, and the brick-and-mortar clinic, MiddletownPT.com, are available resources. I've encountered many individuals who've received misguided advice. Typically, with evidence-based methods and accurate diagnoses, improvements occur. So, persist in seeking solutions. In my perspective, if you haven't improved under your current clinician's care, it's more likely that something crucial is being overlooked rather than an inherent issue. Trust me, the possibilities might surprise you.

Note: The information provided in this blog post is for educational purposes and should not replace professional medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance.